Every month, a translator of Dutch into English gives literary tips by answering two questions: which translated book by a Flemish or Dutch author should everyone read? And, which book absolutely deserves an English translation? To get publishers excited, an excerpt has already been translated. This time you will read the choice of David McKay, who translated work by the likes of Stefan Hertmans and Charlotte Van den Broeck.

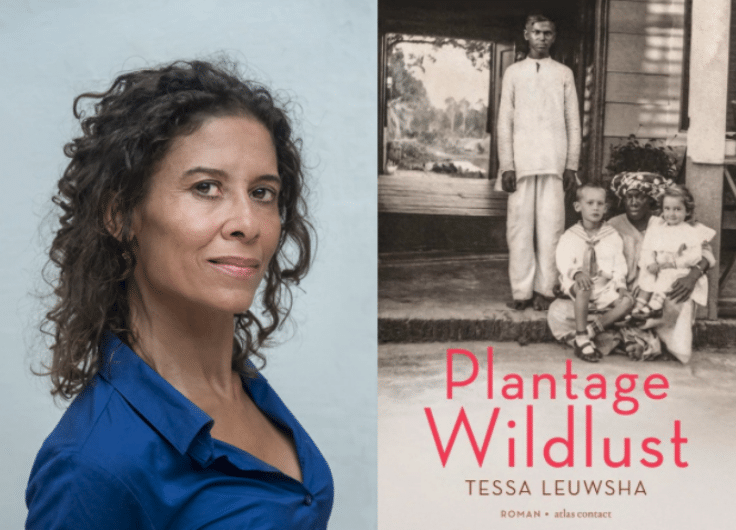

Must-read: ‘On a Woman’s Madness’ by Astrid Roemer

photo Astrid Roemer by Raúl Neijhorst

photo Astrid Roemer by Raúl NeijhorstIn recent years, movements such as Black Lives Matter and developments in post-colonial studies have inspired translators and publishers to take a new and overdue interest in authors of colour and topics of race, racism, and social justice. In the small world of Dutch-English literary translation, this larger trend has led to a number of exciting publications, with several others still in progress. I’m proud to have grappled with themes of Dutch colonialism and racism in my translations of the classics Max Havelaar and We Slaves of Suriname, both of which are must-reads for anyone interested in Dutch culture, literature, or history.

But here I’d like to highlight the very latest in translated Dutch literature: On a Woman’s Madness by the Surinamese and Dutch author Astrid Roemer, translated by Lucy Scott, to be published on 21 February by Two Lines. Astrid Roemer holds a unique place in the Dutch literary world. Her challenging literary experiments, her subtle wordplay, the huge range of her writing, and her profound exploration of post-colonial themes have earned her the highest distinctions in the Dutch literary world, the P.C. Hooft Prize and the Dutch Literature Prize.

On a Woman’s Madness was a critical and commercial success when first published in 1982 and has become recognized as a modern classic. The novel influenced the Dutch feminist movement with its protagonist Noenka, a woman who flees her husband and embarks on a quest for her true identity. The setting and symbolism emphasize Suriname’s vibrant flora and fauna: orchids, fruit trees, serpents. And the characters represent a wide swath of Suriname’s racial and cultural diversity. The first glowing reviews are already in: Publishers Weekly calls the book a ‘classic of queer Black literature’ and describes Scott’s translation as ‘a gift to English-language readers’.

Astrid Roemer, On a Woman’s Madness, translated from the Dutch by Lucy Scott, Two Lines Press, 2023, 284 pages

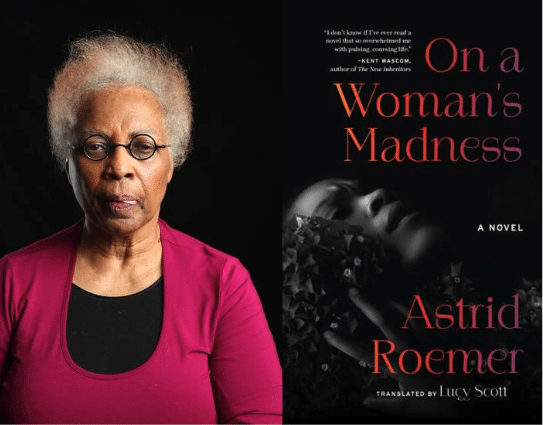

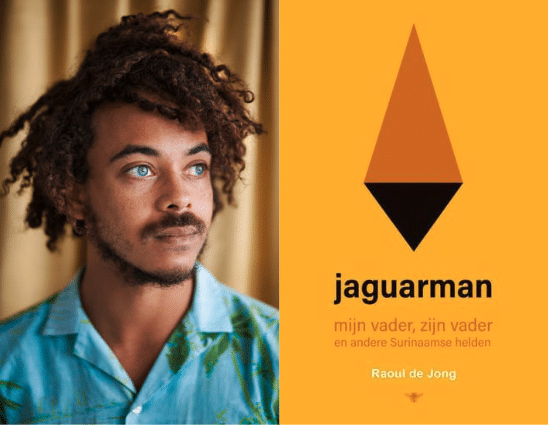

To be translated: ‘Jaguarman’ by Raoul de Jong

One of the most noteworthy contemporary heirs to Roemer’s tradition is Raoul de Jong. An avid globetrotter, De Jong has based many of his books on his travels: four months in West Africa, a trip to northern and southern Italy with an Italian artist, and a trek on foot from Rotterdam to Marseille. He has won major prizes and nominations for his journalism, playwriting, and creative non-fiction. Like On a Woman’s Madness, his recent memoir Jaguarman describes a quest for self: after Raoul manages to track down the Surinamese father he never knew, he travels to Suriname, for the first time in his life, to come to grips with his family history and cultural heritage. Already translated into French and Bulgarian, Jaguarman will speak to anyone who has struggled to define their own identity. It is also a joy to read; De Jong’s stylish, distinctive prose crackles with humour, vitality, and suspense. The reviewer for the NRC Handelsblad writes, ‘Jaguarman is an astonishingly rich book. De Jong drags you into the story, which is full of offshoots and great leaps in time and thought. You effortlessly see through his eyes and are moved and surprised, entertained and shocked. His discoveries become yours.’

Raoul de Jong, Jaguarman, De Bezige Bij, 2020, 240 pages

Excerpt from ‘Jaguarman’, translated by David McKay

Dear thou-who-art-my-forefather,

For these past few years, you’ve been playing a game with me. You’ve sent me signs and I’ve followed them. From Rotterdam to Paramaribo, from Rome to Recife. But every time I came close to treading on your tail, you sped away. We can’t go on like this forever; I think you know that as well as I do. It’s time to take stock. To put our cards on the table. All right, I’ll start. This is not a story about white or black or the Netherlands or Suriname, and it’s not a story about my father, even though all those things play a role. This is a story about you. I’m told you had supernatural powers and those powers have something to do with me.

Is that possible? Is it possible that just because we share a few genes, your actions have influenced my life? When I look at my father and myself, I think the answer must be ‘yes’. For twenty-eight years he wasn’t a father to me, yet we shared everything – much more than just our outward appearance. So it stands to reason there’s also something of my father’s father in me, and of my father’s father’s father. And all those fathers lead me back to you. My father tells me you had the power to change yourself into a jaguar, king of the Amazon, the strongest – and some say the cruellest – animal in the South American rainforest. How did you do it? Who were you? Where did you come from? Where did you get your powers? And why does my father tell me I should leave those powers alone?

This is day one of a seven-day ritual to answer my questions, a ritual described to me in a little gingerbread house with anti-theft grates and a rose garden in a district of Paramaribo called Kasabaholo, ‘Cassava Hollow’, by the seventy-nine-year old Winti priestess Misi Elly Purperhart.

‘What my father told me—could it be true?’ I asked Misi Elly. She was staring at something over my shoulder: a spirit, I thought, but when I turned around all I saw was a car parking across the street.

She let out a secretive laugh and to my surprise quoted the Bible: ‘I, your God, am a jealous God, punishing the children for the crimes of the parents unto…’ – and then with a roar – ‘…THE FOURTH GENERATION!’